How Muscular Millionaire Bernarr Macfadden Transformed the Nation Through Sex, Salad, and the Ultimate Starvation Diet

LA Times Book Review of MR. AMERICA by Mark Adams

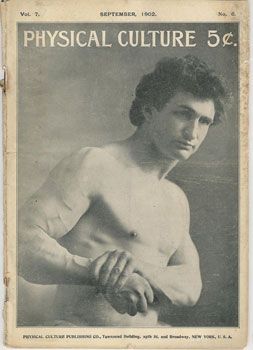

Before Jack LaLanne and Jane Fonda, an odd man with an odd name reigned as America’s health and fitness guru. Bernarr Macfadden championed the benefits of weight lifting and vegetarianism at a time when meat and potatoes was considered a balanced diet and pumping iron injurious folly. His wildly successful magazine, Physical Culture, was the linchpin of a far-flung publishing empire that launched the careers of Walter Winchell and Ed Sullivan.

In “Mr. America: How Muscular Millionaire Bernarr Macfadden Transformed the Nation Through Sex, Salad, and the Ultimate Starvation Diet,” journalist Mark Adams exhumes this long-forgotten icon. Macfadden was a tireless, self-made entrepreneur who thought nothing of walking 25 miles to the office or persuading Eleanor Roosevelt, in the midst of her husband’s first presidential campaign in 1932, to edit one of his publications. He left behind thousands of pages of essays and articles and at least three authorized biographies. He was also an insufferable bore who publicly blamed his wife for causing the death of one of their children in infancy. His belief in eugenics and flirtation with fascism undermined the more enlightened facets of his philosophy.

Adams deftly wrestles this messy, Herculean life into shape. He was born Bernard McFadden in 1868 rural Missouri and endured a childhood that would give Horatio Alger pause. His father drank himself to death when Bernard was 5. His mother died of tuberculosis not long afterward. Weak and sickly, he spent his youth shunted between orphanages and cruel foster homes in the Midwest.

His epiphany came at age 15, when he happened by a St. Louis gym and was mesmerized by the musculature on display. He bought a set of used dumbbells and feverishly worked out. What emerged was a newly named, chiseled form that would turn heads today at Muscle Beach. He adopted a rallying cry, “Weakness is a crime,” that inspired legions to change their lifestyles.

As Adams points out, his timing was excellent. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the exodus from rural America grow apace. Sportsmen, clergy and politicians fretted that the cities would teem with pale, sedentary office clerks. Myriad experts, and quacks, proposed all manner of cures for societal and bodily ills.

Macfadden separated himself from other advocates by taking “the oddball health ideas of a bunch of bushy-bearded nineteenth-century abolitionists and freethinkers and [repackaging] them in a form that was palatable,” Adams writes. Self-promotion and groundbreaking journalism were his instruments of choice. He showed off his buff physique at lectures around the country and within his periodicals, and sponsored the country’s first bodybuilding contest. (One of his discoveries was Angelo Siciliano, better known as Charles Atlas.) He opened spas and health-food restaurants under his name.

Strong views

His primary outlet was Physical Culture, where he articulated a core set of principles, in bold print with multiple exclamation points: Eliminate cigarettes, white bread, sugar and corsets. He railed against prudishness and espoused sexual liberation for women. He published the writings of an impressive roster: boxing champ John L. Sullivan, muckraker Upton Sinclair as well as George Bernard Shaw and Planned Parenthood founder Margaret Sanger. He gave Winchell and Sullivan early gigs at the tabloid Graphic, while future directors John Huston and Sam Fuller found work as reporters.

At the height of his influence, Macfadden had the ear of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt. He was profiled by the New Yorker, and ran (unsuccessfully) for the U.S. Senate. Graphic competed with the bestselling Hearst papers, while True Story was a lowbrow moneymaker that captivated generations of housewives.

With his uncritical support of all remedies alternative, Macfadden could be maddeningly wrong. His “prescription” for premature balding was to tug violently at his hair. Other missteps had more serious consequences. He did not allow his third wife, Mary, to have a doctor present at their children’s births. His kids never received vaccinations because he considered them harmful. In 1922, when his 11-month-old son had seizures, he plunged the boy into a hot bath. The youngster died in Mary’s arms, and Macfadden held her responsible. His faith in eugenics led to an admiration of fascism. According to Adams, “the German martial ideal held an unshakable grip” on Macfadden. Benito Mussolini was a personal hero, and after they met in Europe in 1930, Macfadden agreed to train 40 Italian cadets on U.S. soil. He told a reporter, “There are times when I believe that America needs a Mussolini, as never before.”

Perhaps inevitably, Macfadden fell out of favor in post- World War II America. Adams concludes that his influence waned in part because the mainstream started to accept his views. A balanced, low-fat diet is healthful; aerobic activity does exercise the heart; walking and deep breathing are vital and soothing.

A muscular shadow

Macfadden died in 1955, at age 87, and a generation of acolytes has preserved his legacy. LaLanne used the medium of television, and a snug jumpsuit, to persuade the masses to get off the couch. Later, Woodland Hills-based publishing mogul Joe Weider helped to popularize weightlifting and bodybuilding; he employed an Austrian muscleman named Arnold Schwarzenegger much like Macfadden had used Charles Atlas. Another influential publisher, Jerome Rodale, followed Macfadden’s teachings and produced the magazines Prevention as well as Organic Gardening and Farming. Most recently, his embrace of periodic and sustained fasting has won over many critics.

The roller coaster that was Macfadden’s life sometimes threatens to overwhelm Adams’ narrative. The rollicking details pile up, so much so that this reader lost track of Macfadden’s wives and lovers, and Adams offers minimal analysis of the junk-science treatments Macfadden advocated. Those criticisms aside, “Mr. America” is an entertaining, enlightening read that, in expanding on Robert Ernst’s 1991 academic-press biography, gives Macfadden his overdue legacy.

In the appendix of the book, Adams tests three diets from Macfadden’s repertoire. Regimens of walking, fasting, raw foods, milk and intense mastication follow, with impressive results. After one round, Adams reports, he had lost “four inches from my waist . . . . My energy level was high and . . . my digestive bug and lung problems disappeared.” Even from the grave, it seems, Bernarr Macfadden continues to educate and shape America.

Visit the McFadden website HERE.